(5.5.17–27) Footnote 1Īt stake, in short, is the question of the plausible historicist provocation lurking inside this imperative speech.

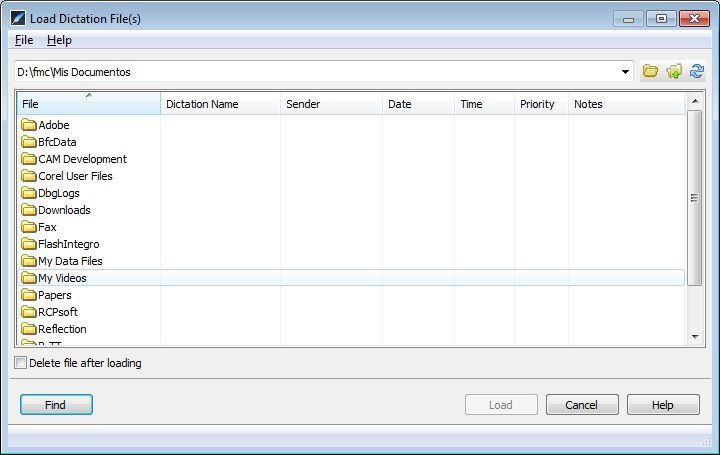

#Express scribe 5.13 free download full

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, That struts and frets his hour upon the stage, Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player There would have been a time for such a word.Ĭreeps in this petty pace from day to dayĪnd all our yesterdays have lighted fools To illustrate this point, Strauss conjured a literary echo: Historicism, in sum, “culminated in nihilism” (18). Human communities devoid of objective criteria to tell a good choice from a bad one became, therefore, groundless. The fact that these standards are dictated by the relative whims-“free choice”-of individuals precluded, he believed, their claim at objectivity.

He objected that “all standards suggested by history as such proved to be fundamentally ambiguous and therefore unfit to be considered standards” (18). History no longer understood as a universal force but as a set of particular frames where every people’s past, heritage and situation is brought into focus became the only available source for objective and principled “knowledge of what is truly human, of man as man” (17). Members of that school characteristically counterclaimed that “all human thought is historical and hence unable to grasp anything eternal” (12). The “historical school” emerged, he argued, in reaction to the French Revolution and “to the natural right doctrines that had prepared that cataclysm” (13). In the first chapter of Natural Right and History (1950), philosopher Leo Strauss launched a memorable attack on “historicism”.

This article is published as part of a collection to commemorate the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death. In the final analysis, Macbeth gets the last word, one no oracular predictive or postdictive consummation is able to efface. By exposing the logical complicity between providentialist prophecy and historicist interpretation, this article contends that Shakespeare obtained, in Macbeth, ironic-critical distance from contemporary historiographic teleology, and that he thus sheltered himself in advance from the progressive-moralist, at bottom apocalyptic, arrogance of neo-historicist critics like Stephen Greenblatt or Richard Wilson. Self-validating prophecy emerges, in this reconsideration, as the pivotal, paralogic speech act in a play that reads like a parody of verification. Moreover, the scarcely noted fact that the debate for and against historicism-encouraged by thinkers like Hegel, Lukács, Strauss, Aron or Popper-tends to capitalize on the hermeneutic affordances of a play like Macbeth, brings the historical (perhaps historicist) provocation of the play all the more sharply into focus. Although Macbeth is not stricto sensu a history play, its dominant concern with the paralogisms of time forces the reader to reconsider its relationship with history.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)